This episode contains disturbing language.

Joe Richman from PRX’s Radiotopia, this is Radio Diaries. I’m Joe Richmond. Today on the podcast, we’re bringing you a story we produced for This American life at the center of the story is a book called The Education of Little Tree. In the book. A boy named Little Tree is five when his parents die, he then goes to live in the woods with his Cherokee grandparents who teach him to respect the earth, to take only what he needs from nature, and to appreciate the fundamental human virtues of respect and tolerance. The Education of Little Tree was first published in the mid-1970s as an autobiography by Forest Carter. It’s been a staple of high school, English, and history classes for decades.

Student I really liked it. I found that, uh, I really connected to Little Tree. I felt like he was a lot like me sort of, we’re both trying to become better people. I’m trying to learn to be good person, become who I am, be a man. But, uh, so it was a Little Tree.

Joe Richman That it’s a student from Masconomet Regional High School in Topsfield Massachusetts, where students have gathered to discuss the book after their sophomore English.

And there’s one thing I should tell you about The Education of Little Tree a thing that some of you may already be aware of, the book is a lie. It’s not an autobiography. It’s all made up. Today, the true story of the untrue story of The Education of Little Tree, the story begins with the most famous racist, political speech in American history.

George Wallace Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. This is the inaugurate day of my inauguration as governor of the state of Alabama. And this day-

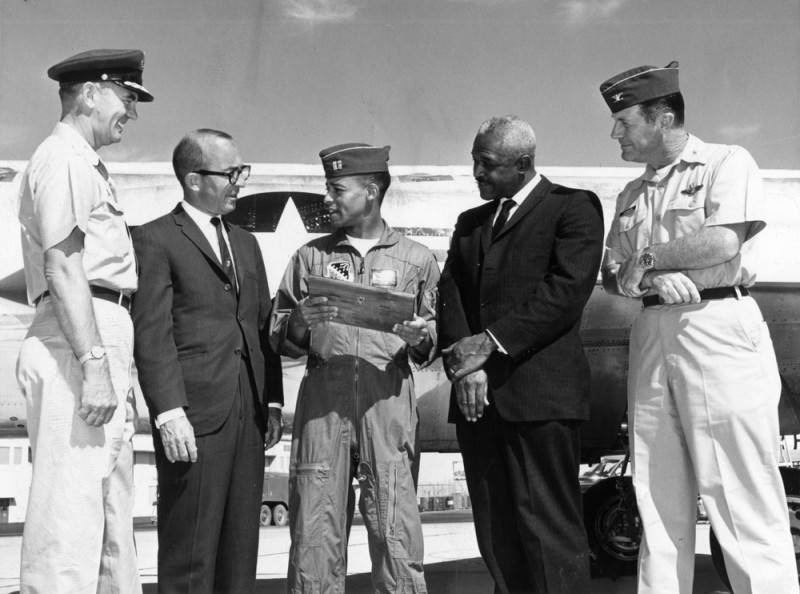

Joe Richman During the Civil Rights era, George Wallace, the governor of Alabama, was the personification of Southern racism. He was the one who famously stood in the schoolhouse door to prevent two black students from enrolling at the University of Alabama. But the moment that first really catapulted Wallace onto the national stage was his inauguration speech in 1963.

George Wallace Let us send this message back to Washington that from this day we are standing up and the heel of tyranny does not fit the neck of an upright man.

Wayne Greenhaw He was promising that he was going to stand alone for the Southern cause, the cause of the white people.

Joe Richman Wayne Greenhaw was a young reporter in Alabama in the 1960s. He remembers listening to this speech and the famous words “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

Wayne Greenhaw It’s vehement, it’s mean-spirited, it’s hateful. It’s like a rattlesnake was hissing it almost. But it’s beautifully written.

George Wallace In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny. And I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever. [CHEERING]

Joe Richman This speech was a catalyst for much of the violence that followed. Just a few weeks later, Birmingham police used dogs and fire hoses on protesters. And later that same year, there was the bombing of a church in Birmingham, where four little girls were killed on a Sunday morning.

Today what most Americans know about George Wallace are those words– “segregation now, segregation forever” –even though they weren’t actually his words. Behind those words, behind that speech was an entirely different person– Asa Carter, the poet laureate of Southern racist speech writing.

Wayne Greenhaw “Segregation now, segregation forever” became Wallace’s symbol. It all came from Asa Carter’s pen. And nobody could write it any better than Asa.

Radio Host It’s time for another essay on liberty by Asa Carter.

Asa Carter Thank you. The one great truth is race. Each race has a character, and each race–

Joe Richman That’s Asa Carter. He was a staunch segregationist. He started his own splinter branch of the KKK in Alabama. He wrote and published a white supremacist magazine. And every week, radio stations around Alabama would air Asa Carter’s 15-minute liberty essays, which were about everything from his views on racial purity to the dangers of integration, communism, and rock and roll, all delivered with literary flair.

Asa Carter That’s why the left-winger so much wants to make our history a shrouded nothingness of confusion, to twist the songs of our fathers into bebop rhythms, and to degenerate our mores into a cacophony of chaos.

Radio Host You’ve been listening to Asa Carter with an essay on liberty.

Joe Richman In 1956, Asa had his KKK group attack singer Nat King Cole on stage, because Asa hated the idea that a Black musician was performing for White women. Asa reserved special hatred for the Jews, who he felt were really to blame for the corrupting power of popular culture. He once said, “The Negro is the virus, but it’s the Jew that inserts it in the veins of America.”

And then in 1962, Asa got a new gig as George Wallace’s speechwriter Ron Taylor was a good friend of Asa Carter’s.

Ron Taylor They’d call him and tell him what they wanted, you know. And they’d just give him a cup of coffee and two packs of Pall Malls, and he could write you a 20-minute speech in 30 minutes.

Joe Richman Asa’s speeches helped George Wallace become governor in 1962. But within a few years, the arrangement was falling apart. Tom Turnipseed was George Wallace’s campaign director back then.

Tom Turnipseed Times changed, and Wallace wanted to cool it a little bit. He didn’t want to just come out and say, I’m a segregationist. He didn’t want to use that terminology anymore. He wanted to be more moderate.

Asa’s views were too extreme. And so Gov. Wallace didn’t need Asa anymore. Asa would call me up and talk with me on the phone some. And he was resentful because he just felt like he was being ignored.

Here’s the guy that wrote the famous, iconic speech. And now Wallace, he won’t listen to me anymore. He won’t talk with me. He won’t take my advice. And so he felt used, I think, by Gov. Wallace.

George Wallace –upon which I am about to enter to the best of my ability, to the best of my ability–

Joe Richman George Wallace was elected governor again in 1970. But this time, his inauguration speech was very different from the speech that Asa Carter had written back in 1963. Wallace said, “Alabama belongs to all of us, black and white, young and old, rich and poor alike.”

Reporter Wayne Greenhaw was on the steps of the capital at the time covering Wallace’s inauguration address. And he happened to run into Asa Carter.

Wayne Greenhaw After the speech, I found Asa out on the back steps of the capitol. And we sat on the stairs, talking. And he started crying. He said, “Wayne, George Wallace sold out. He’s betraying us to the liberals of this nation.” He stood up and turned around and said farewell.

Asa Carter Well, I am just an old rebel, I reckon that is all I am. For this carpetbagger government, I do not give a dadblame. I’m glad I fit again’it. I’ll keep fighting until we won. And I don’t want no pardon for nothing that I’ve done. This is Asa Carter. May God bless you. And I thank you for listening.

Wayne Greenhaw And that’s the last time I ever saw Asa Carter. He just vanished like he dropped off the face of the earth.

Chuck Weeth My name is Chuck Weeth.

Betty Weeth I’m Betty Weeth.

Chuck Weeth And I and my wife ran a bookstore in our town of Abilene, Texas. In 1975, this man came walking in the store and said, “I’d like to introduce myself. I’m Forrest Carter.”

Betty Weeth He wore a cowboy hat, blue jeans, and had a mustache.

Chuck Weeth He’s dark complected, smile wrinkles around his eyes. He said he was Cherokee and he was raised by his grandparents back in Tennessee. No electricity, no running water. And I liked him. From the very start, I liked him.

Joe Richman This new guy in town, Forrest Carter, quickly became a fixture in Abilene, Texas. Chuck and Betty Weeth say Forrest was outgoing and friendly. He told people in town he never had any formal education and spent his adult life wandering between ranch jobs. And he entertained everybody with stories about his Cherokee childhood.

Betty Weeth We had him to our house several times for supper, just because you wanted to hear a little more about this life, which I wasn’t familiar with at all.

Chuck Weeth He was sort of the underdog of the American culture, and you were cheering for him. And you just grew to love him.

Joe Richman Chuck and Betty Weeth knew Forrest was a writer and that he’d written a Western. Forrest told them he was sending copies of the book to people in Hollywood.

Chuck Weeth He’d already approached–

Betty Weeth Clint East–

Chuck Weeth –Clint Eastwood. And lo and behold, Clint Eastwood was well enough taken by this first book, Forrest told us, he’s planing to make a movie of it, which indeed he did do, called The Rebel Outlaw– Josey Wales.

Movie Narrator He lives by his word. And he lives for revenge. Clint Eastwood is the outlaw Josey Wales.

Josey Wales Why, you gonna pull those pistols or whistle Dixie?

Joe RichmanDuring the time all this was happening, Forrest was hard at work on another book, a book he described differently than his first one. That was a novel. This was an autobiography. And he was calling it The Education of Little Tree. An orphan Cherokee boy raised by his grandparents who grows up to write a Hollywood movie starring Clint Eastwood– it was made for TV.

Barbara Walters Good morning. This is Today. I’m Barbara Walters with Jim Hartz.

Joe Richman And in fact, in 1975, Forrest was invited to New York to be a guest on The Today Show with Barbara Walters.

Chuck Weeth She introduced him as an Indian who had busted broncos all over the Southwest.

Joe Richman While viewers around the country were being introduced to Forrest Carter, there were some people back in Alabama who recognized a man they hadn’t seen in years. Ron Taylor remembers watching that morning as Forrest Carter told viewers he was the storyteller to the Cherokee Nation.

Ron Taylor He had that black hat pulled way down. [LAUGHS] He just tanned himself up, grew a mustache, lost about 20 pound. But as hard as he tried, he couldn’t fool the folks back home. I literally got down on the floor laughing and rolling around. Call the wife, “Asa’s on TV! He’s on with Barbara Walters.” And I’m just rolling around on the floor laughing because Asa had pulled it, you know. He had fooled them.

Joe Richman By the time The Today Show aired around the country, reporter Wayne Greenhaw had already been onto the story for a few months, the story that Asa Carter and Forrest Carter seemed to be the same person. The tip-off came when Wayne happened to write a review of Forrest Carter’s first book, the one that became a movie. After the book review appeared in the paper, Wayne ran into an old friend of Asa Carter’s, Ray Andrews.

Wayne Greenhaw And Ray said, “Old Asa’s got you fooled too, huh?” And I said, “What are you talking about?” And he said, “I saw you wrote a review of Asa’s novel.” I said, “That’s Forrest Carter.”

And Ray grinned and laughed and said, “Yeah, that’s old Asa. Asa’s Forrest Carter.” Well, I thought, what in the world? And it just bumfuzzled me.

Joe Richman After that original bumfuzzle, Wayne started to make calls

Wayne Greenhaw I got in contact with Eleanor Friede, who was a editor at Delacorte Press. And she had discovered Forrest Carter. And when I told her the story, she said, “Oh, no. It couldn’t be the same guy. He’s such a sweet, gentle, fine man. He would never say a word about anybody because of the color of their skin. And I know he’s not anti-Semitic, because my husband and I are Jewish, and we’ve had him to dinner a number of times. And he’s always just as nice as he could be. It just couldn’t be the same man.

Joe Richman In fact, the editor told Wayne she was about to publish Forrest Carter’s autobiography, The Education of Little Tree. Wayne told her he would still love to talk to Forrest Carter himself, because he was writing a story for The New York Times about all this

Wayne Greenhaw Sure enough, in a few days, Forrest Carter called me. And he said, “You’re this Greenhaw writing about me.” And I said, “Yes, sir.” And he said, “Now, you don’t want to hurt old Forrest, do you, boy?” And I said, “Come off of it, Asa. I recognize that voice. I know you, you know me. We’ve drunk beer together.”

I said, “I’m not trying to hurt you, but this business of Little Tree is not a true story.” I said, “I want to tell the truth about what is going on here.” He said, “Oh, boy, you know I don’t do things like that.” And he pretty much after that hung up.

Joe Richman Wayne had no idea why Asa was doing what he was doing. Why had he changed his name and become a storyteller to the Cherokee Nation? Why had he gotten a tan, slimmed down, and grown a mustache? And how did he expect to get away with going on TV and talking to Barbara Walters in a fake Texas accent?

All Wayne knew was Forrest Carter was lying. He wasn’t a Cherokee. This wasn’t a memoir. And his name wasn’t Forrest.

Wayne Greenhaw And the story ran in The New York Times August the 26th of 1976 with the headline, “Is Forrest Carter really Asa Carter? Only Josey Wales may know for sure.”

Joe Richman Wayne though his New York Times article was going to set off a huge scandal. But a curious thing happened after the article came out, something that surprised Wayne Greenhaw. And it probably surprised Asa and Forrest Carter. What happened was nothing.

A few months later, Forrest Carter’s autobiography, The Education of Little Tree, was published. And in fact, after Forest slash Asa died in 1979, the book just became more and more popular. In the late 1980s, The Education of Little Tree caught a wave of rising interest in all things Native American. And people seemed to identify with its themes– humility, tolerance, living in harmony with nature.

A new paperback edition included a foreword by an actual Cherokee writer who called the book deeply poignant and compared it to Huck Finn. More than a million copies were sold. In 1991, the book reached number one on The New York Times Nonfiction Best Seller List. In 1994, Oprah Winfrey recommended it on her TV show.

Every once in a while, a new article would come out revealing yet again the racist past of the book’s author, and some small things would change. The New York Times moved the book from the nonfiction to fiction category. Oprah eventually took it off her book list. Some Native Americans said the book was full of stereotypes and was a complete fraud, but the Cherokee guy who wrote the foreword stood by it. It seemed that no matter what came out about the background of the book, its popularity continued. Today you can find it in Barnes & Noble in the Native American section.

Dan Carter Most people who loved the book simply could not imagine that a former Klansman, racist, anti-Semite, this person couldn’t have written The Education of Little Tree.

Joe Richman This is historian Dan Carter, who, by the way, isn’t related to Asa Carter. But he is writing a biography of the man. And he hits on the question that’s at the center of the whole story. Is it possible that something happened in the heart of Asa Carter? Did he change? Was he a reformed racist trying to break from his shameful past? Or was he just trying to make a buck? Or was it all just a joke on his new-age liberal readers?

What does it mean that the man who wrote this–

George Wallace And I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.

Joe Richman –could also write this?

Man One time grandma told me, when you come on something good, first thing to do is share it with whosoever you can find. That way the good spreads out where no telling how far it’ll go.

Joe Richman Here’s Asa Carter.

Radio Host In the South, we have 98% Anglo-Saxon races, not counting the niggers.

Joe Richman The only group Asa Carter hated more than blacks were Jews. So what does it mean that Forrest Carter created the character of Mr. Wine, a generous and sympathetic Jewish peddler who befriends Little Tree?

Man Mr. Wine said if you learn to place a value on being honest and thrifty, on doing your best, and on caring for folks, this was more important than anything.

Joe Richman How could someone talk with so much venom–

Asa Carter We shall submit to Negro dominion another day, another hour, another month. Behind every ballot is a bayonet and the red blood of an Anglo-Saxon who holds it.

Joe Richman –and still write something so sweet?

Man I could feel something more, as Grandma said I would. Mon-o-Lah, the Earth Mother, came to me through my moccasins. I would have liked to live that time forever, for I knew I had pleased Grandpa. I had learned the way.

Joe Richman Actually, “the live in harmony with nature” message isn’t really that surprising. You might expect a white supremacist to be nostalgic about living off the land. And someone can certainly write hate speech and still love nature. But what most leaders took from The Education of Little Tree is a message of tolerance and respect for Native Americans and for the African American and Jewish characters in the book. In fact, the villains in this story aren’t the minorities. They’re the white politicians.

For many people who love The Education of Little Tree, the only way to make sense of it was to take the book at its word and to believe that Asa Carter had truly changed. It wasn’t an act, but a sincere transformation. Yes, OK, he wasn’t a Cherokee orphan. But in this heart, he had become Forrest Carter. And Exhibit A for this point of view, for “the people can change and people do change” point of view, is Asa Carter’s former boss George Wallace, the man he wrote speeches for.

TV News Host Primary elections are being held Tuesday. And George Wallace is trying a come back, trying to become governor again.

Reporter At black meetings, Wallace repudiates his former racist stance.

George Wallace And whether or not you agreed with me in everything that I used to do and agreed to, I know that you do not. I too see the mistakes that all of us made in years past.

Joe Richman This is footage from George Wallace’s last campaign for governor in 1982. He was actually in a wheelchair– the result of an assassination attempt. And he was in the midst of what would be known as his apology tour, going around the state to black churches and civic groups, anyone who would have him and saying, I was wrong.

One of the civil rights leaders Wallace apologized to was Congressman John Lewis, who still has a visible scar on his head from famously being beaten by Alabama state troopers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the march to Selma, Alabama.

John Lewis And I remember the occasion so well. It was like someone confessing to their priest or to a minister, just telling me everything and asking me about everybody, that he never had an opportunity to meet with Martin Luther King Junior, to meet Dr. King. He wanted people to forgive him. He said, “I never hated anybody. I never hated black people.” He said, “Mr. Lewis, I’m sorry.” And I said, “Well, Governor, I accept your apology.”

I believe people have the capacity to change. I think he was sincere.

Joe Richman George Wallace was a lifelong politician. And it’s impossible to say if his change of heart was authentic or not. But the people he was apologizing to believed it. In his last election as governor of Alabama in 1982, he won with 90% of the black vote. Wallace continued his apology tours long after he left public office.

So George Wallace represents the transformation-is-possible theory. To people in Abilene, Texas, who are friends with Forrest Carter, the Cherokee writer, that’s what happened to Asa Carter. He pulled a Wallace. Here’s Chuck and Betty Weeth.

Betty Weeth I personally think the Forrest Carter I knew was sincere. The other life he seemed to have had as Asa Carter, I just sort of dismiss it.

Chuck Weeth I agree with that. I guess it’s sort of that feeling that give a man a chance, he might change himself. And we felt like, well, he tried to change himself and he succeeded with us. I didn’t like Asa Carter, I’ll guarantee you. But I did like Forrest Carter.

Joe Richman There’s another person who has some thoughts on this, one of the few people who knew both Forrest and Asa Carter.

Carol Boyd He was Uncle Asa to me. He wasn’t Uncle Asa, the white supremacist. He wasn’t Uncle Asa, the staunch segregationist. He was Uncle Asa. So for me, it was my uncle wrote this wonderful book.

Joe Richman Carol Boyd is the daughter of Asa Carter’s brother. She’s never spoken about any of this on the record before. All of Asa’s family members have kept silent for years. Like many of them, Carol was sheltered from most of the details of her uncle’s racist past. The main thing she knew about her uncle– he was the true author of The Education of Little Tree.

Joe Richman So when did you first read The Education of Little Tree?

Carol Boyd I guess I was a senior in high school when I first read it. I loved it. I fell in love with it. I actually cried. I just think it’s a beautiful story. I still read it today.

Joe Richman Carol describes herself as politically liberal. She voted for Obama twice. And to her, that book is all the proof she needs that in the end, her uncle wasn’t so so different in his view from her.

Carol Boyd Just to have the ability to write that book, whether you present it as an autobiography or not, just to have that in you I think says that there is a good part of this person. I would hope that people would choose to believe maybe he found a softer side in his older years. And maybe he did change.

Ron Taylor Did he change? That’s the question you asked. No. No, no, no, no, no. Not at all. Not at all did he change.

Joe Richman This again is Ron Taylor, one of Asa Carter’s friends from the early days back in Alabama. Ron would describe himself as the opposite of politically liberal. And he’s chief proponent of theory number two–

Ron Taylor No, no, no, no. No.

Joe Richman –Asa Carter did not change.

Ron Taylor You know, I could do like some and just say, oh, he didn’t really mean that. He didn’t this, that, and the other, but did. He did. And to refute it, like say Wallace did and people like that, then that makes it their whole lives lies before. I mean, old Wallace, after they wheeled him out in his wheelchair, and he apologized for everything he ever was.

But Asa Carter wasn’t going to apologize. He felt like he was right. And he lived it and he died it. He just didn’t change. He was Asa Carter.

Joe Richman There are some interesting clues that support Ron’s theory. Many of the supposed Cherokee words in the book Asa completely made up, just nonsense words. Mon-o-Lah, the Earth Mother, comes up a lot. Not a word. The name Forrest, it’s not about communing with nature. It comes from Nathan Bedford Forrest. Never heard of him? He was the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

And even the fact that the book is told from the point of view of a Cherokee kid, some white supremacists, it turns out, had a thing for Native Americans. KKK members sometimes bragged about being part Native American. It’s the noble savage trope that goes back to DW Griffith films and much earlier. It may seem counter-intuitive, but to Asa Carter, it was perfectly reasonable to glorify Native Americans while hating blacks and Jews.

And there’s one more thing– Asa’s inscription in the copy of the book that he gave to Ron.

Ron Taylor And this is my copy of it. It has gotten rather tattered. Here’s signature page. It says “For Ronny, my friend whose loyalty to the Southern cause has made us comrades. Forrest ‘Asa’ end quote Carter.” The only time he ever signed it that way.

Joe Richman All this leads Ron to a third theory, one I wasn’t expecting. Asa didn’t change, and he didn’t fake a change. The Education of Little Tree is exactly what Asa Carter always believed. Everyone else just misinterpreted it.

Ron Taylor Well, one way you look at it, it’s a tree hugger’s book. It’s all about nature and this, that, and the other. And the other way it’s a right-wing, “government, leave me alone” book. The government took Little Tree and put him in an orphanage, you see. And the government passed the whiskey tax. And the government did this. And the government did that to the American Indian. And that’s the way I read it. I was shocked when I found out other people was understanding it differently.

Joe Richman Ron feels that The Education of Little Tree is speaking directly to him and to what he believes. But I asked Ron, what if it’s the other way around? What if you’re the one who’s wrong?

Ron Taylor [SIGH] Well, I would like to know myself. If it’s what I think it is. What I think it is, I think he wrote it for me, me and my ilk. But I don’t know that. Because it’s probably been more interpreted the other way– the other way being the tree hugger way as opposed to my anti-government, anti-cities and government intrusion in our daily lives, that type thing.

I don’t know. I know how I took it. But I also know that there’s many or more people took it the other way. Asa Carter. I wish I knew what he thought. I really do. But I honestly don’t know.

Joe Richman I don’t know myself what to make of the whole thing. But while I was working on this story, I picked up a new copy of The Education of Little Tree and I started to read it to my two daughters. They’re loving it. Of course, they don’t know the back story. And I’m not sure when I’m going to tell them.

For me, it’s kind of confusing to read the book and know the history. Like, am I a sucker for just reading it? Every once in a while, I’ll come across a passage, like when five-year-old Little Tree sees a hawk kill a young quail. It makes him sad.

So his grandfather teaches him “the way,” which is about taking only what you need and about how nature weeds out the small and the slow so the species can grow stronger and more powerful. And I think, is this some white supremacist secret code of racial purity? Or is it just a lovely lesson about the circle of life and not being greedy

A few days ago, I was sharing a pastry with one of my daughters. I tore it in half and held out the two pieces. She chose the small one. And then she looked at me and said, “I have learned the way.” For her, the book has nothing to do with small government or racial superiority. It’s all about trying to understand people different from yourself, just being a good human being.

Whatever Forrest Carter believed in his heart of hearts, it’s safe to say this is a book that Asa Carter would have hated.

A few years ago, we held a contest with NPR and

A few years ago, we held a contest with NPR and