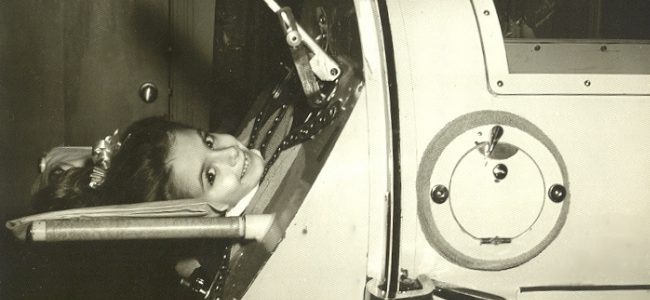

Joe Richman, Host: In the first half of the 20th century, the disease known as polio myelitis (my-eh-LIGHT-is) panicked Americans. Just like Covid today, polio stopped ordinary life in its tracks. Tens of thousands were paralyzed when the virus attacked their nervous systems. Many were left unable to walk. In the worst cases, people’s breathing muscles stopped working, and they were placed in an iron lung: a large machine that fit their entire bodies from the neck down. Vaccines brought an end to the epidemic in the 1950’s and gradually, iron lungs became obsolete. The last ones were manufactured in the late ‘60s.

But there are two people in America who still use an iron lung. One of them is Martha Lillard. She’s able to breathe on her own during the day but still relies on it at night. Today on the show: My Iron Lung

Martha: Okay, this is the sound of the motor.

My name is Martha Lillard and I live in Oklahoma and I have spent 66 years of my life sleeping in an iron lung. It’s a big metal cylinder with a cot that rolls in and out. It has leather bellows on the end of it. When the bellows goes out, that’s when you breathe in. At the end of the day, when I get in there, it’s like a very deep breath and a lot of pain that I’ve been having throughout the day, pretty much is gone.

Martha: But the main problem I’ve had with it is just parts. There came a point in the nineties, the 1990s, the iron lung was breaking down. Well, it was just womping and banging. And I was just afraid it was going to quit working. So I started looking for another iron lung called hospitals who had them in their basements. They’re in museums but they didn’t want to get rid of them. And then I found this guy in Utah that had one.

Martha: It probably scares me more than I would like to admit. The iron lung breaking down and I wouldn’t be able to breathe. And, you know, I mean, if it breaks down, I don’t last too long.

Martha: Around 1952 I think, it was really a serious epidemic year for polio. 52 to 53

Archival: Deserted beaches became a sign of the crippler’s presence, no swimmers or boaters where crowds would normally be in summertime. A children’s playground with not a child in sight.

Martha: I remember my mother being careful. So she pretty much kept us at home.

Archival: Children were not allowed to leave their own yards. It was as though people had shut themselves up in their houses, trying to hide from an unseen and deadly enemy. Not daring even to venture upon the streets.

Martha: But I had been wanting to have my fifth birthday party at our local amusement park. It was just a small little park. And I think that’s where I caught the polio.

Martha: The day before I got sick, my neck was kinda sore, my throat was sore. But I went to bed and went to sleep. And when I woke up, it hurt really bad. I couldn’t raise my head up off the pillow. And I could hear my dad in the bathroom brushing his teeth and. My mom was putting the laundry in in the dryer,

So I just kind of wanted to lie there and listen to that for a little while, because I knew once I told them about this, it was going to be very different. After a few minutes, I called them in there and I just told them, “I have polio.”

Archival audio: As epidemics grew in community after community, a steady stream of victims was rushed to hospitals. Men, women, children, as always, especially children.

Martha: I was in what they call isolation. It was in the top room of the hospital. I just deteriorated real fast. I turned blue from lack of oxygen. So then they determined to put me in the iron lung

Archival audio: Ladies and gentlemen you are looking at the business end of an iron lung. And that sound that you’ll hear is the air being forced into the lung so that the patient can breathe.

Martha: The minute they put me in and I woke up and I felt so good because I been feeling so bad. It was like it fixed everything. I was breathing again.

There was a young nurse there and she said, would you like a coke? Mother only allowed us to drink cokes on the weekend. And I said, “Sure.” And she gave me a coke and I drank the whole bottle. And she said, “Would you like another one?” And I said, “Sure!” She got me another bottle and I drank it. She said, “Would you like another one?” I just thought, “oh man, you know, I’m getting away with murder here!”

What I didn’t realize was that for four days I hadn’t been eating or drinking.

Martha: There were two people in iron lungs just beside me. There was Bobby Slayton and she was 15 and there was the lady. I only call her the lady ‘cause I really don’t know what her name was. She was 21. And after a while the lady died, but Bobby survived.

Martha: I was in the hospital six months and Dr. Garrison told me I could come home around Christmas. I did have to pretty much be in the iron lung full time. Mother would get me out for 30 minutes, 40 minutes, an hour. The focus was to be independent, to get as much like I had been as before.

Martha: I went to school for an hour a day. I couldn’t sit up in the classroom for very long because of the pain in my back. It was very painful to sit in a chair for even an hour. And then in the eighth grade, they decided to let us attend school with what they called the school-to-home phone for the handicapped and it was a speakerphone and you could have that in your home and you just turned it on and you could press a button and talk to the teacher and you could hear what the teacher was saying.and the students, you know they were really friendly to me over the speakerphone and I got to know some of them, but it was hard not being able to identify all of them.

Martha: never got to do all the things that I wanted to, but there was a friend of mine who taught me to look in a way that I’d never really looked at things before. She was my neighbor, Karen Rapp. Karen taught me to look at a small world. She noticed a lot of insects and we would get on the ground and check out the ants and how they functioned.

We would build little villages on the ground, tiny little grass huts and things, and Adobe houses. I learned to look at small things and to really appreciate them. There’s much more to see if you really look for it.

Martha: Being handicapped affected my relationships. When I was young, a lot of the parents of boys didn’t want their sons dating someone who was handicapped. But then later it didn’t seem to really bother them. And I met Ray in 1989. We were together for, well, about 28 years up until he moved into the nursing home

Now I could never have children. I just already knew because of my breathing that I couldn’t do that.

Martha; Well it’s difficult, you know, because basically I’m alone all the time. My sister does come over at eight o’clock in the evening to help feed the dogs and open some cans for me. But I have gotten trapped in the iron lung a couple of times.

Martha: Like last October, we had an ice storm come through here, a terrible ice storm. and I had no power and ordinarily my generator would come on. But the battery had died on it. So I was lying there in the cold. It’s like being buried alive almost, you know, it’s so scary. And so I thought I’d better call 9-1-1. They said, “I’m sorry, this number isn’t available.” So obviously the cell phones, the towers weren’t working. I was having trouble breathing and I, I remember saying out loud to myself, “I’m not going to die. I’m not going to die.”

And then the cell phone finally started working. And so people came from 911, so then everything was okay.

[machine sound]

Martha: I don’t like having to be in the iron long. I would rather, I didn’t have to use it. that was my big goal was to be free of that.

But I never did really become independent of it.

Martha: People have said, “Martha doesn’t want to be modern, you know, she’s dependent on the iron lung.” I have assessed this thing. And I have tried every kind of ventilation, the NEV 100 positive pressure, the Monaghan, the Thompson, the Emerson Wrap, which was basically a big piece of plastic that wrapped around your body. I’ve tried all the forms of ventilation. The iron lung is the most efficient and the best and the most comfortable way.

So I just wanted people to understand that it’s not, “oh, I want to be in the iron lung.” That’s not true. I would rather not need it at all. But sometimes when I get in there, I say, “thank you!” You know?” It feels wonderful to get into it. It’s the thing that’s been there that saved my life. And I know that it’s the only thing that’s kept me here.

Joe Richman: Thanks to Martha Lillard for sharing her story with us.

Also thanks to Erin Kelly, who introduced us to Martha, and to Paul Alexander, who also lives in an iron lung. And thanks to widespread use of vaccines, the U.S. has been polio-free since 1979.

Our story was produced by Alissa Escarce and Erin Kelly. It was edited by Ben Shapiro, Deborah George and myself. The Radio Diaries team also includes Nellie Gilles, Mycah Hazel and Stephanie Rodriguez.

Radio Diaries is part of the Radiotopia network from PRX, a collective of the best podcasts on the planet. We’re supported by the National Endowment for Humanities… and from listeners, like you.

Thanks to Taylor Phelan and the Cranes for their song, “Iron Lung.” I’m Joe Richman, thanks for listening.